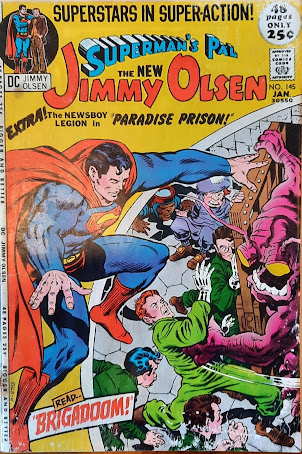

A monster named Charlie, with large, yellow searchlight eyes and a body like a disembodied purple heart, suddenly comes out of a prison door and randomly snatches you off the street. Your friends can do nothing as they watch you vanish, taken away to fight, in your army green, the flesh already gone from your hands as if just the touch of the creature strips off skin to the skeleton.

Reading Jimmy Olsen # 145 (January, 1972), published 50 years ago today, 18 November, 1971, it’s hard not to feel the times rip through the pages, the war in Vietnam only one thin layer of meaning deep in what is ostensibly a children’s story about Jimmy Olsen, the Newsboy Legion and the pursuit of a mythical kingdom, the Scottish fairy tale of Brigadoom.

The older brothers of younger readers must have lived moment to moment as they waited in fear for their number to come up in the draft lottery. ‘Angry Charlie’, like the American soldiers’ ‘Charlie’ nickname for the Viet Cong, is certainly a ‘…livin’, breathin’ nightmare’ and like the Stones’ classic ‘Sister Morphine’ released only a few months earlier, those brothers must have wanted someone, something to ‘…turn my nightmares into dreams.’ The reality of the draft era was random selection, injury, death, napalm and by 1971, heavy drug use by soldiers¹ and by youth at home.

As Jimmy and the Legionnaires gaze at the mythical creatures at Scotland Yard, they marvel at the fairy tales brought to life, in all their grandeur, ugliness and wonder. The most fearsome is Angry Charlie who is the most active, reaching through the prison bars as the boys fear he may break out. The Scottish policeman Glowrie tranquilises Charlie and says ‘Aye! He’s gettin’ a bit drowsy now,, is Charlie.’

If only that were true in Vietnam for the soldiers and on the streets for the counter-culture. Morale amongst US soldiers was low, the process of ‘Vietnamisation’ allowing the South Vietnamise regime to lead the fight had already taken its toll on US troops who knew ‘the ARVN weren’t willing to fight their own war.’² 1972 would see some of the biggest, bloodiest battles of the war.³

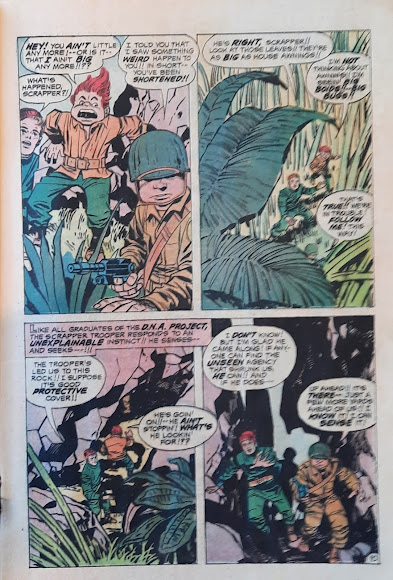

Home and away, people were tired. As Jimmy and Scrapper on land and Flippa Dippa and the other newsboys by sea in the Whizwagon, approach Brigadoom, the gap between the comics fantasy and the world outside begins to reduce, both figuratively and literally. Jimmy and Scrapper, already dressed in military green, begin slogging through foilage as impenetrable as a Vietnamise rừng nhiệt đới.⁴ A strange compressor wave shrinks them in size and leaves are now the size of huge paddies. Already difficult, their quest for the mythical Scottish city becomes even harder, each step facing a bigger obstacle.

What lies in wait for them is a mirage, not Brigadoom but the Evil Factory, the rival Apokoliptian DNA experimentation plant to the Project. Captured by Mokkari and Simyan, Jimmy is laid on the operating table where he is subject to ‘…millions of gene nuclei shot through his open pores…’, nuclei which are ‘…regressive and powerful.’

Kirby has used the idea of reduction and expansion before in Jimmy Olsen, where occupants of a tiny planet rise up to our size, dressed like horror movie characters, symbolic of our fears, all our attempts to minimise what we are afraid of eventually loom up before us where we have to face them⁵. Here the two macabre medical malfeasants cut our heroes down in size so they can control them. Then they go one step further and attempt to turn back evolution.

The ideas of the Sixties were so powerful and so challenging to the State, that every attempt was made by official agencies to undermine and discredit counter-cultural groups⁶, to minimise the impact the kids were having, to return them to safe, comfortable 1950s boys and girls, to turn back the clock and regress to the previous conservative way of life. Woodstock nation stood for the opposite, for the plurality and progression of ideas, a new kind of society.

Jimmy becomes the personification of all this, reduced and regressed, he smashes his shackles, reborn as a freckled Conan, all violence and 1950s bruiser. He wouldn’t be out of place in Philip Zimbardo’s August 1971 experiment at Sanford University⁷ where Zimbardo used students to show the deindividuation and dehumanisation of prison life, as ‘guards’ in anonymous uniforms regressively became increasingly violent in their roles in the experiment.

Kirby seems to be saying that anyone can be brutalised,

anyone can be transformed from their best to the worst because we have both qualities

inside us. This issue began with a monster, now the spotlight is on the monster in us, prisoners of our own heart.

Things are not what they seem

Please, Sister Morphine, turn my nightmares into dreams

Oh, can't you see I'm fading fast?

And that this shot will be my last

Sweet Cousin Cocaine, lay your

cool cool hand on my head

Ah, come on, Sister Morphine, you better make up my bed

'Cause you know and I know in the morning I'll be dead

Yeah, and you can sit around, yeah and you can watch all the

Clean white sheets stained red’

Sister Morphine by The RollingStones (written by Marianne Faithfull, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards). Released as a single 21 February, 1969 by Marianne Faithful and a slightly different version by the Stones on the album Sticky Fingers,

23 April, 1971.

¹Hastings, 455-7. In 1971, 60 per cent of US soldiers smoked marijuana, the super-strong Buddha grass. In 1969 only two per cent had tried heroin, by 1971 it was 22 per cent, almost a quarter.

² Ibid, pg. 505.

³ Ibid, pg. 519.

⁴ Vietnamese for 'jungle'.

⁵ See my commentary on Jimmy Olsen # 143

⁶ COINTELPRO and CHAOS were FBI and CIA programmes respectively, designed to discredit the counterculture and maintain the status quo.

⁷ For more info see the official website of the experiment. Footage appeared on the recent Apple + TV series, '1971''

Research this article:

Comics:

-Comic Book Creator # 24, Fall 2020

-Comics Journal # 134, February 1990 (Jack Kirby

interview by Gary Groth)

-Jack Kirby Collector # 5, May 1995 and # 8, January 1996

-Mike’s

Amazing World of Comics website

-The indispensable Kirby & Lee: Stuf’ Said! (Jack

Kirby Collector # 75: TwoMorrows)

-The equally indispensable Old Gods, New Gods (Jack Kirby

Collector # 80: TwoMorrows)

Popular culture:

-Helter Skelter, the True Story of the Manson Murders

(Vincent Bugliosi with Curt Gentry, W.W. Norton, 1994)

-There’s A Riot Going On (Peter Doggett, Canongate, 2007)

-Time Magazine, May 11, 1970

-Uncovering the Sixties (Abe Peck, Pantheon, 1985)

-Vietnam: An Epic History of a Tragic War (Max Hastings,

William Collins, 2019)

Michael Mead is a 55-year-old New Zealand comic book

collector, who likes to think he can do "contextual" commentary

reviews of old comics, asking: "where does this story come from?",

looking at the social, political, cultural times it came from, the state of the

comics industry, the personal and creative journey of the writer or artist, the

personal journey of the reader as a child and as an adult.

As part of this, he is vain enough to think he can bring

new insights into Kirby's Fourth World comics and so, on the 50th anniversary

of publication of each issue of Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen, Forever People, New

Gods and Mister Miracle, he will publish a contextual commentary. This is his 30th

of a projected 48 Fourth World commentaries. Check out his earlier entries on

this blog and tell him to stop talking so pretentiously in the third person for

God's sake!