Kamandi Jimmy feverishly tears up the evil factory of the State in Jimmy Olsen # 146 (February, 1972), published 50 years ago today, 21 December, 1971 as Jack Kirby shows us how the culture increasingly saw its rebellious youth as long-haired, violent, inarticulate, angry, animals.

Kirby’s transformation of Jimmy Olsen, both the character and the comic from his first issue, Jimmy Olsen # 133, takes the formerly freckle-faced fop on a wild, unpredictable journey, mirroring the passage of American Sixties youth. Once a conformist, high school, Jerry Lewis-type physical comedian, Jimmy becomes a counter-cultural leader, a warrior. He changes physically into a more muscular, vocal, independent personality, it brings him into conflict with the State represented by Superman.

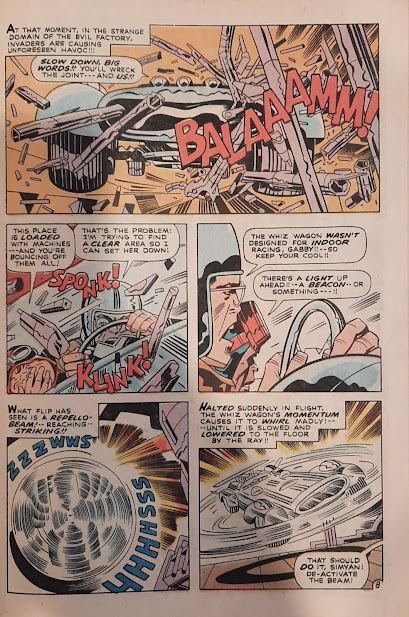

Jimmy and his protégé Newsboy Legion pursue Apokoliptian forces, they hunt for the Evil Factory where Darkseid’s minions Mokkari and Simyan foment their regressive devolved dehumanisation of Jimmy. In the previous issue, Jimmy fought ‘Angry Charlie’ a monstrous stand-in for the threat of the Vietnam draft and fight against the Viet Cong.¹ Now Jimmy is the monster, a raging caveman and in his look, surely a prototype for Kirby’s Kamandi, the first issue of which the King would draw the same month Jimmy Olsen # 146 was published.²

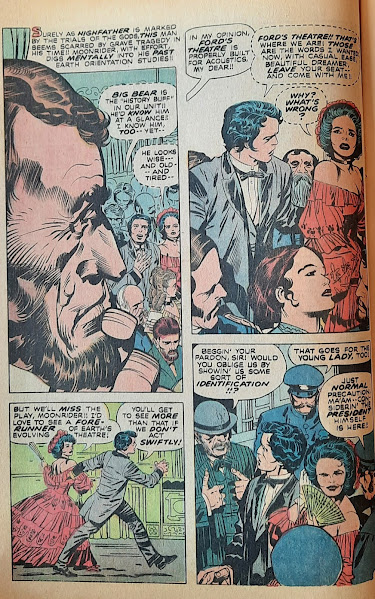

If Jimmy Olsen # 145 was a metaphor for how youth felt about the draft, the threat of being forced to fight and kill Viet Cong and Viet Minh North Vietnamese, then this issue is its counterpoint. Jimmy as Kamandi monster is how the State, how conservative parents, how Nixon’s so-called Silent Majority saw the counter-culture, as ‘homo-disastrous’, a foreground, brutalised, long-haired, angry threat which kept coming to tear down everything that the older generation valued.

May 1971 had seen the May Day protest against the Vietnam war with 12,000 protesters arrested in Washington D.C., the largest mass arrest in United States’ history.³ June 1971 saw the publication of the Pentagon Papers in the New York Times, showing how successive American administrations had lied to the public about Vietnam, like an evil factory crafting misinformation. In September 1971, 43 people died in the Attica prison rebellion. The State felt under attack and factions of the Movement such as the Weather Underground rejected peaceful solutions to ending the war in Vietnam, perpetrating domestic terrorism instead.

Jimmy as caveman monster is all counter-cultural rage. The remnant of a now divided Movement, destabilised by internal disagreements and by specific State-run programmes whose job it was to put youth in a spin.⁴ Tranquilised by drugs, Kamandi Jimmy initially ‘goes under quite promptly’, perhaps as certain parts of the Youth Revolution had, as he attacks his Evil Factory captors. Mokkari and Simyan aim to ‘take the fight out of him’ but are surprised when they learn Jimmy has escaped their trap, freed by Scrapper and Scrapper Trooper.

Jimmy attacks his friends, Scrapper, Scrapper Trooper, the Newsboy Legion in the Whiz Wagon, who have escaped doom themselves, literally going off track as they escape the fiery doom of an Evil Factory death trap. Each side of the culture feels the other is leading it to death, youth feared Vietnam, age feared societal disintegration. Jimmy is single-minded in his violent solution to end the Evil Factory as he leads a parade of prehistoric, screeching, roaring, brawling, wild animals on a rampage to the heart of Evil, like a phalanx of hippies storming the Pentagon.

The peaceful patience of Jimmy’s movement has run out. Brutalised, monsterised, he becomes a symbol, he confirms the worst stereotypes of all those fearful parents and succeeds by destruction, obliterating the Evil Factory as the Newsboy Legion rides on his caveman coattails.

It seems Jimmy and the boys have triumphed. Returned to their own world, seemingly whole and alive, the Evil Factory, ‘…a complex structure, destroyed by its own evil’. The feeling of the final page though is more like relief and loss, than victory. Good has only prevailed through violence, rage. Good is divided. Is this really how we want to win, is this the Sixties dream realised or just the end of a nightmare?

¹See my commentary on Jimmy

Olsen # 145, ‘Prisoners of our own heart’ .

²Jack Kirby Collector # 80, pg. 6.

³From the Lawrence Roberts 2020 book, ‘Mayday

1971: A White House at War, a Revolt in the Streets and the Untold History of

America’s Biggest Mass Arrest’, pg. xxii.

⁴COINTELPRO and CHAOS were FBI and CIA programmes

respectively, designed

to discredit the counterculture and maintain the status quo.

Research this article:

Comics:

-According to Jack Kirby (Michael Hill, Lulu, 2021)

-Comics Journal # 134, February 1990 (Jack Kirby

interview by Gary Groth)

-Mike’s

Amazing World of Comics website

-The indispensable Kirby & Lee: Stuf’ Said! (Jack

Kirby Collector # 75: TwoMorrows)

-The equally indispensable Old Gods, New Gods (Jack Kirby

Collector # 80: TwoMorrows)

Popular culture:

-Helter Skelter, the True Story of the Manson Murders

(Vincent Bugliosi with Curt Gentry, W.W. Norton, 1994)

-There’s A Riot Going On (Peter Doggett, Canongate, 2007)

-Time Magazine, December 20, 1971

-Uncovering the Sixties (Abe Peck, Pantheon, 1985)

-Vietnam: An Epic History of a Tragic War (Max Hastings,

William Collins, 2019)

Michael Mead is a 55-year-old New Zealand comic book

collector, who likes to think he can do "contextual" commentary

reviews of old comics, asking: "where does this story come from?",

looking at the social, political, cultural times it came from, the state of the

comics industry, the personal and creative journey of the writer or artist, the

personal journey of the reader as a child and as an adult.

As part of this, he is vain enough to think he can bring

new insights into Kirby's Fourth World comics and so, on the 50th anniversary

of publication of each issue of Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen, Forever People, New

Gods and Mister Miracle, he will publish a contextual commentary. This is his 33rd of a projected 48 Fourth World commentaries. Check out his earlier entries on

this blog and tell him to stop talking so pretentiously in the third person for

God's sake!