‘I'll put flowers at your feet and I will sing to you so sweet

Do you hear the voices in the night, Bobby?

They're crying for you

See the children in the morning light, Bobby

They're dying’

(‘To Bobby’ by Joan Baez, November, 1971)

By December 1971, what was left of the Movement to End the

War in Vietnam was splintered, under attack from within and without. Woodstock Nation

was described as a ‘fantasy’ by a former, musical ally.¹ Yet the needs of youth,

the desire to be heard, the reality of the draft and fighting and dying in

Vietnam were as real as ever.

Alpha power still had to bend and listen to the young, to restore them from the ‘fire pit of destruction’ to the ‘tranquil green of the morning’. In Forever People # 7 (March, 1972), published 50 years ago today, 2 December, 1971, Jack Kirby reaches across time and generations and hears the forever cries of his people in the night.

When we left Mark Moonrider, Vykin, Big Bear and Beautiful Dreamer last issue they had been wiped out of existence by Darkseid, presumed dead. The remaining member of their New Gods number, Serifan, was alone in his living super-cycle. It’s like an image for the insurgent, now flamed-out Sixties, forgotten, obliterated, lost, alone. Forever People # 7 opens with those lost, lonely voices, New Genesis’ Council of the Young pleads with Highfather, the Moses-like leader of the good planet to save their comrades.

It is the smallest, the youngest of the young that appeals directly to the heart of Highfather’s Alpha power. Esak brings authority and youth together as he makes the case for the restoration of the Forever People, even though they broke the rules: ‘Not against your edicts, Highfather! But for our friends. Is this not a world of friends?’ Esak, in his age-defying wisdom, contrasts the way power is used, the destructive firepit of Darkseid and the ‘power to which lightning dances’ wielded by Highfather who reveals that Mark Moonrider, Vykin, Big Bear and Beautiful Dreamer are not dead by merely misplaced in time.

As Kirby takes us to different time periods where the four forevers have foundered, he sets out his philosophy, his vision of the kind of society he believes in, where youth and age co-exist equally and violence, exploitation, militarism are rejected. The values of the Forever People are at odds with armed revolution, with a resigned acceptance of capitalism or the pursuit of shrill, ideological orthodoxies.

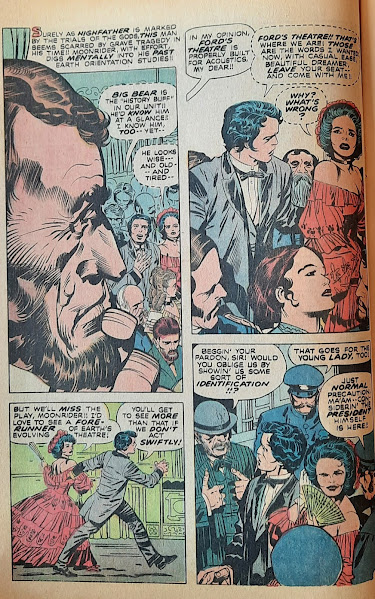

Mark Moonrider and Beautiful Dreamer land at Ford’s Theatre in Washington D.C. on April 14, 1865, where they try to prevent the death of President Abraham Lincoln. In an age of political violence, like the one they left in 1971, Mark and Dreamer rush to stop John Wilkes Booth as he seeks to revive the Confederate cause, ‘Now we must be true to ourselves. We must do what is true to highfather. We must try to stop a killing!’ They fail but their non-violent values are on full display.

Vykin is stranded in 1513 Florida with Ponce de Leon’s troops as they search for gold. Vykin leads them to it but his own interests are in ecology. education, harmony. Ponce’s exploiters later receive due reward for their avarice.

Big Bear alights in ancient Britain circa fifth century just as the Romans are leaving, in an image that recalls the ongoing withdrawl of US forces from Vietnam.² His interest is in learning from history and he calls for reconciliation between the remaining British factions, one fighting against the occupiers, the other allied with an imperialist army, at the end of the War.

The last Forever Person, Serifan battles Glorious Godfrey and his Justifiers, who are ‘absolved of all guilt’ in their murderous intent. Serifan defends himself from attack but is overwhelmed. Highfather saves all five with the ‘alpha bullet’, finding them, restoring them, ‘where I have meant it to be.’

Joan Baez and others such as the Rock Liberation Front³ failed in their attempts to radicalise Bob Dylan, the Who and other artists who refused the weight of singing for the Revolution. Jack Kirby, through his Fourth World characters, set out a path of real dissent from the ‘terrible collision of power’ between opposing cultural forces, away from death and destruction, far from strident ideological voices, his duty was ‘to provide the alternative’, a world of friends, a revolution of the heart.

¹Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner, said Woodstock Nation was a ‘fantasy’ in a November 11, 1971 article, spurred by a rather ironic dispute over whether or not yippie Abbie Hoffman had stolen parts of his book, Steal This Book. Wenner wrote, ‘As long as there are printing bills to pay, writers who want to earn a living by their craft, people who pay for their groceries, want to raise children and have their homes, Rolling Stone will be a capitalist operation.’ (as quoted in Peck, pg. 276).

²President Nixon announced the withdrawl of 45,000 troops

from Vietnam by February 1972, in a White House news conference on 12 November,

1971. See

New York Times transcript.

³A.J. Weberman's Rock Liberation Front (RLF) agitated for major musicians to write political music for the youth Revolution. Weberman's major target was Bob Dylan. He failed to radicalise Dylan but later succeeded with John Lennon but not before being forced to recant his vehement criticism of Dylan after the intervention of other members of the RLF, David Peel, Jerry Rubin, Yoko Ono and John Lennon. Doggett, pgs. 461-465.

Research this article:

Comics:

-Comics Journal # 134, February 1990 (Jack Kirby

interview by Gary Groth)

-Mike’s

Amazing World of Comics website

-The indispensable Kirby & Lee: Stuf’ Said! (Jack Kirby

Collector # 75: TwoMorrows)

-The equally indispensable Old Gods, New Gods (Jack Kirby

Collector # 80: TwoMorrows)

Popular culture:

-Helter Skelter, the True Story of the Manson Murders

(Vincent Bugliosi with Curt Gentry, W.W. Norton, 1994)

-New

York Times, 13 November, 1971

-There’s A Riot Going On (Peter Doggett, Canongate, 2007)

-Time Magazine, November 29, 1971

-Uncovering the Sixties (Abe Peck, Pantheon, 1985)

-Vietnam: An Epic History of a Tragic War (Max Hastings,

William Collins, 2019)

Michael Mead is a 55-year-old New Zealand comic book

collector, who likes to think he can do "contextual" commentary

reviews of old comics, asking: "where does this story come from?",

looking at the social, political, cultural times it came from, the state of the

comics industry, the personal and creative journey of the writer or artist, the

personal journey of the reader as a child and as an adult.

As part of this, he is vain enough to think he can bring

new insights into Kirby's Fourth World comics and so, on the 50th anniversary

of publication of each issue of Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen, Forever People, New

Gods and Mister Miracle, he will publish a contextual commentary. This is his 31st

of a projected 48 Fourth World commentaries. Check out his earlier entries on

this blog and tell him to stop talking so pretentiously in the third person for

God's sake!

No comments:

Post a Comment